Tailor Made

John Haberin New York City

Many Ray at the Met

"Dada cannot live in New York," Man Ray insisted. "All New York is Dada, and will not tolerate a rival." Maybe so, but it would not often let him get on with the ordinary business of painting or of living in New York. Could that why he left the city as a young man for Paris, where he got along just fine?

He got the bug as an artist early, studying at New York's National Academy of Art and the Art Student League, but they left him with a stale Postimpressionism except for one thing: painting for him was never less than in motion. He must have felt a kindred spirit at New York's 1913 Armory Show in Marcel Duchamp, whose Nude Descending a Staircase set Cubism itself in motion and made a sensation. He had tasted Modernism at the gallery of photographer Alfred Stieglitz and radical politics in art with the Francisco Ferrer Center, an anarchist center, in 1912, but now he and Duchamp were creating motor-driven glass plates. With Katherine Dreier they formed the Société Anonyme and became the exemplars of Surrealism in New York. Leave Dada to Paris.

Accompanying himself

It would not let him define himself so easily as a fine artist. He had too little money and too much creativity. Born Emmanuel Radnitzky in 1890 to tailors and Russian immigrants in South Philadelphia, he moved with his family to Williamsburg, in Brooklyn, at age twelve. And he kept making commercial art to support himself as he grew. His younger brother renamed them Ray, and he would later admit to no other last name, though he was familiarly just plain Manny. It has nurtured a kind of visual poetry and a retrospective.

He was still drawing and painting, although barely. An instinctive poetry enters his work equally though plays on objects and plays on words. In The Rope Dancer Accompanying Herself with Her Shadow, in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, colored planes evoke a European circus—rope in the air and the dancer swirling it above. Fragments of color take life from a burst of light within her outlines, which takes shape without a brush. At a time when America trailed way behind Europe, Ray was the exemplar of Surrealism in New York and in life. It would carry him to Europe in 1921.

He is exploring an art of abstract geometry, but with little regularity or repetition. It pushes him as close as art comes to abstraction at the very moment it embarks on a course between the continents and between world wars. It is an art of at once poetry, imagery, and words. It moves easily between color and black and white, each wrapped up in surfaces and textures. It moves between icy highlights and clotted color. Highlights and shadows soften into something neither quite two or three dimensional.

Ray all but gives up painting, in favor of photography and a medium he all but invented, photograms. He exposed objects to photo-sensitive paper and exposed the paper to light. As rayograms, they have taken his name. They supply an intricate record of his studio and the barest hints of his life. A palette knife itself becomes a threat. If this is the scope of his world, who knew?

Part of its power is its strangeness, even to Alfred Stieglitz. Someone had to save it all. Things turn out to have been smaller than you might ever have guessed and certainly more disordered. They constrain the very movement of things, for an artist obsessed with kinetic art. The marvel is that it looks so elegant and so made to last. Is this all there is to work on paper and to art?

It may well be all there is, at least to Ray's art, and the Met goes all in. With "When Objects Dream," it commits fully to photography of both people and things. His manner of exposure can leave either one ghostly and gaunt, with an abundance of bodily shadow, as if dying before one's eyes. It is a stellar and abundant art. Ray kept company with such Surrealists as Jean Cocteau and Tristan Tzara as well as Marcel Duchamp and such socialites as the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven and Kiki de Montparnasse (or Alice Prin). He shared enough with their elegance and with Duchamp that he designed a chess set as well in polished wood.

The heritage and the threat

This is Ray's second retrospective in just fifteen years. He appeared at the Jewish Museum in 2010. It cannot claim a longer and fuller career. As an American, he had to leave Paris on the eve of World War II and never found his footing again. Yet he lived till 1976, and the Met will not let you forget it. It just cannot deliver much of anything in terms of late work and second thoughts.

As curators, Stephanie D'Alessandro and Stephen C. Pinson with Micayla Bransfield adopt quite a maze, so that you may never know just how far you have progressed. The Whitney this fall describes Pop Art as a second Surrealism in America, and it does not mean May Ray. Was he so much as aware of the burst in the 1960s of avant-garde film? One thing for certain: the Met has three different films. They are among the high points.

He returns often to sculpture and appropriation, in a body of work that comports not just with Duchamp, but with Robert Rauschenberg and combine painting decades later as well. Stranger still, he never leaves altogether behind his origins as a Jew. A tailor's family will never let him forget it. He wraps a sewing machine in felt for the heaviness of a body. He adds sharp nails to the bottom of a clothes iron for the threat, as Gift. He may or may not be ironic.

He makes rayograms from string that he might once have used in fabric. He suspends clothes from above hangers as the ultimate mobile. He may finally have taught kinetic sculpture to float free. He is to the end the creator of Champs Délicieux (or "delightful fields"), but also much else. He cannot put altogether behind the living heritage or the darkness. He leaves it to you to guess at more.

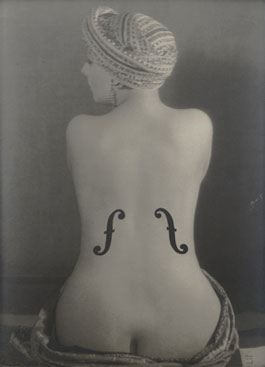

He adds violin sound holes to Kiki de Montparnasse as perfect nude figure, for Le Violon d'Ingres. It means a hobby that has become a compulsion. Perhaps darkness for him is itself delight. He titles a metronome Object to Be Destroyed, and he destroys it. Its incessant ticking becomes itself a threat.

You may prefer to remember a smaller body of work, from an artist who traditionally seems to have only greatest hits. There are drawbacks to a large show tilted so heavily toward rayograms. Still, Ray makes the case for both abstraction and photography at the very heart of modern art. He makes the case, too, for something inconceivable. America made art history earlier than you may ever have dreamed, beginning in Brooklyn. And it was a nation of immigrants even more then.

Man Ray ran at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through February 1, 2026. A related essay reviewed his 2010 Jewish Museum retrospective.