9.8.25 — Who Needs Painting?

Who needs painting anyway? Who, for that matter, needs paint? Maybe no one, but you can still be grateful for “Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction” at MoMA through September 13. And I work this together with a review of weaving for Jovencio de la Paz as a longer review and my latest upload.

The question has come up again and again, from the moment Robert Rauschenberg found the materials of a “combine painting” in the debris of art and life. It came up when Tristan Tzara could endlessly repeat Dada and refuse to call it art. Denial could itself be art, by the very definition of conceptual art.  It could also be an imperative, as long “pure painting,” some said, refused to ask who gets to exhibit painting in the first place, baring his (male) art school credentials and his soul. Wall paint still had its uses, for how else could a curator keep the wall clean enough for erudite text, damning or explaining it all. Postmodernism and diversity insisted on it.

It could also be an imperative, as long “pure painting,” some said, refused to ask who gets to exhibit painting in the first place, baring his (male) art school credentials and his soul. Wall paint still had its uses, for how else could a curator keep the wall clean enough for erudite text, damning or explaining it all. Postmodernism and diversity insisted on it.

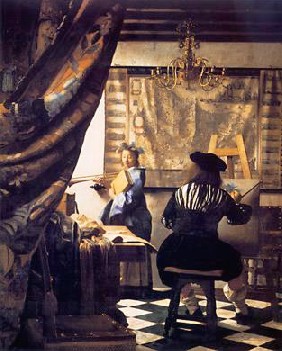

Painting’s very life came for a while to reside in its material being. And its material being, it often seemed, came to reside in anything but paint. Still enough of a Luddite to resent weaving by anything but by hand? As recently as twenty years ago, I could not help noting just how often artists treated craft as testimony to traditions as diverse as a day in the galleries. The weave of fabric could play the role of drawing and colored threads the part of paint. Refuse to stretch a canvas and it becomes a hanging.

My own encounters with tapestries has all but lost its novelty, and allusions to East Asian, African, Islamic, Native American, and Latin American craft have lost much of their specificity as well. That is not to say that the art fails—or fails to address a real need. A snip here and a loop there and you have a curtain, a carpet, a tablecloth, or a home. MoMA, though, has in mind something else. It pushes weaving not to its origins, but back to the future. It sees a new beginning where people have long looked for one, in modern art.

It is not the first show to interweave history and contemporary art. Museums everywhere feel the pressure these days to include new voices, because museum-goers want what they know and what patrons can afford—not dead people, but the living. Just last year came “Weaving Abstraction” and “Crafting Modernity“—and I dare you to remember which is which. The first looked to the Incans for Minimalism’s grid. If its handful of contemporaries included Anni Albers, Sheila Hicks, Lenore Tawney, and Olga de Amaral, well surprise, for here they are again at the Museum of Modern Art. Suffice it to say that none of them is Incan.

Puzzled by the promise of “Modern Abstraction”? Was there a premodern abstraction, and can MoMA quit before things get too postmodern? Try not to split hairs or unravel all the threads. The curators, Lynne Cooke and Esther Adler, proceed more or less by artist. If the working compromise between chronology and motif breaks down now and then, it has a point. It is asking just what holds weaving and abstraction together.

Puzzled by the promise of “Modern Abstraction”? Was there a premodern abstraction, and can MoMA quit before things get too postmodern? Try not to split hairs or unravel all the threads. The curators, Lynne Cooke and Esther Adler, proceed more or less by artist. If the working compromise between chronology and motif breaks down now and then, it has a point. It is asking just what holds weaving and abstraction together.

So who needs painting—and, for that matter, who needs weaving? The show has no apology for reweaving history. It is finding a place for craft in the austerity and creativity of modern art. It can then discover a greater role for women. Curators have been out to recover the female half of couples that changed the face of art, including Anni Albers (apart from Josef Albers) in Minimalism, Sonia Delaunay (apart from Robert Delaunay) in Orphism, and Sophie Taeuber-Arp (apart from Jan Arp) all over the map. They get things off to an impressive start, but can the momentum last—and I answer with what the exhibition really shows next time.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.